As I write this, the US stock markets are kicking off 2017 by reaching for record, all-time highs. So why doesn’t it feel like everyone is exuberant?

Clients have been sharing a general unshakable sense of unease or mistrust. It’s understandable. Rising tides of populism and anti-elitism swept the Western world in 2016, bringing fringe political movements to the mainstream and changing up the political paradigms. These changes have introduced even more uncertainty in a world where unprecedented central bank intervention has already upped the ante post-Great Recession.

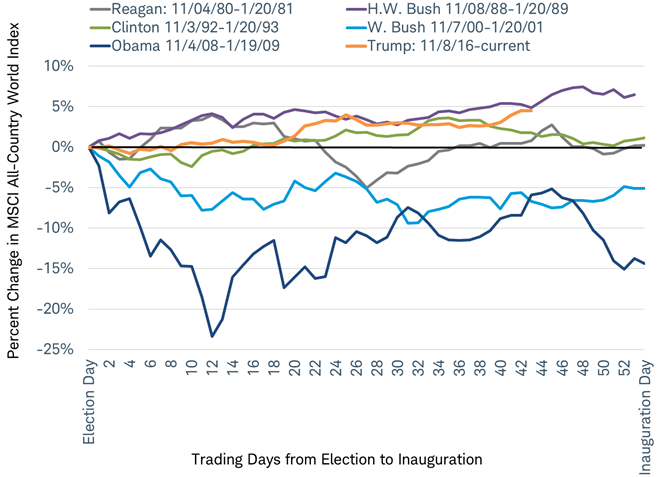

And yet the markets have remained relatively calm. After a quick sell-off and rebound following the UK referendum, the election of a political outsider and self-pronounced Mr. Brexit” for the US presidency has given way to one of the least volatile global stock markets seen in any presidential transition over the last forty years (see below).

So what happened to the uncertainty? Doesn’t the market care? Has everyone gone crazy?

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg data as of 1/6/2017.

Your Crystal Ball Can’t Help You

As we’ve discussed before, volatile stock market periods can introduce a strong temptation to time the market: to sell and wait for a better time” to own stocks. But one-directional markets can also bring those familiar emotions to surface. After all, we get told time and time again that markets go up and down, risk is a necessary condition for return. So when the market starts looking impervious to the newsfeed, it starts to feel suspicious, even unstable.

The challenge with that line of thinking is that it presumes that the stock market and the economy (and the policies that shape it, the news outlets that report on it) operate on the same timeline. Over time, of course, stock market returns should correlate with underlying economic performance. But the short and intermediate-term hold no such promises. Consider, for example, the fact that many of the slowest growing countries (i.e. the developed world) have outperformed the fastest growing countries (emerging markets) over the last five years.

That’s because economic growth is looking at where we were. It may say something about the trajectory we are on, but it mostly looks in the rear-view mirror. Stock markets, meanwhile, capture expectations about future growth and how certain or uncertain that growth appears. That word expectation is critical. It means the next movement of the stock market could have far more dependence on better” or worse” than good” or bad” in the absolute sense of those words. This is how bad news can turn out fairly innocuous, provided it was not as bad as initially feared.

In that light, you can look at the current world, and it’s nearly impossible to be fully convicted of any of the following, plausible narratives: 1) the market is failing to fully account for the uncertainty of the incoming Trump administration and we will pay later in terms of heightened volatility and/or below-average returns; 2) the market is rational because Trump’s campaign rhetoric will be modified and rationalized by the Washington establishment and we won’t actually see that much change or uncertainty in the end; 3) the market had already priced in the uncertain political landscape going into this election year, and our historical returns were lower than what they otherwise could have been; we’ve already paid for the probable challenges ahead.

Uncertainty Doesn’t Have to Be the Enemy

All of this is to say that the investor forecasting game – which we never played to begin with – is a hard one, whether you are dealing with changing political landscapes or the status quo. Returns don’t necessarily come when you would expect them to arrive, which means you have to be prepared to capture them wherever and whenever they materialize.

That means staying invested in spite of uncertainty. And that’s okay, provided we have prepared our portfolios to withstand a variety of possible outcomes. We do that by having a clearly defined investment plan that owns no more stocks than we need or can afford. We do that by having discipline around the implementation of that investment plan so we make smart, risk-based decisions rather than emotional ones. And we do that by making sure we have an adequate cash cushion for expected liabilities so that we can ideally avoid ever being forced sellers of stocks.

Patience is Still a Virtue

In January of 2016, the markets were falling and I wrote here about patience as an edge individual investors have in investing. I will stress it again today as markets are buoyant. The idea is called time arbitrage” and it suggests that you have a longer time horizon than many of the investment managers out there trying to boost their performance via short-term trades. That means that, provided your portfolio is appropriately structured, you can afford the patience to wait for the returns to come whenever they deign to appear, capturing the profits left on the table by more impetuous investors. And you can avoid the problematic (and potentially destructive) temptation to time the markets in the meantime.